This is bigger than borders

Russia is attacking our future

we are fighting back: with truth, law and courage

Indigenous leaders, youth activists, human rights defenders and NGOs have filed a historic climate lawsuit against Russia. They risked everything - and now they need you.

WHat is the russian climate case?

It is more than a lawsuit. It’s a call for justice from two courageous Russian NGOs (Ecodefense and Moscow Helsinki Group) and 18 brave individuals — Indigenous leaders, climate activists, and human rights defenders — who took Russia to Europe’s top human rights court.

Why? Because Russia is one of the world’s top polluters. Because it is ignoring climate science, criminalising peaceful protest, and silencing the voices trying to protect the planet.

In 2023, these courageous people filed a legal case at the European Court of Human Rights. But the court process has stalled. For two years, their lawsuit has sat ignored.

They’re not asking for sympathy: they’re demanding action. The Court must fast-track this case before it’s too late and give clear guidance to Russia on its obligations to protect us all.

meet the people behind the case

These aren’t just names on a legal document: they are people who risked their safety and freedom to defend nature, rights, and truth. They come from across Russia: the Arctic tundra, Siberian forests, Moscow streets. Now, many live in exile. Their courage is why this case exists.

Some cannot show their faces, but their voices matter.

Andrei Danilov

Sámi indigenous defender | Kola Peninsula

“I want to preserve my people, my land, for the future generations.”

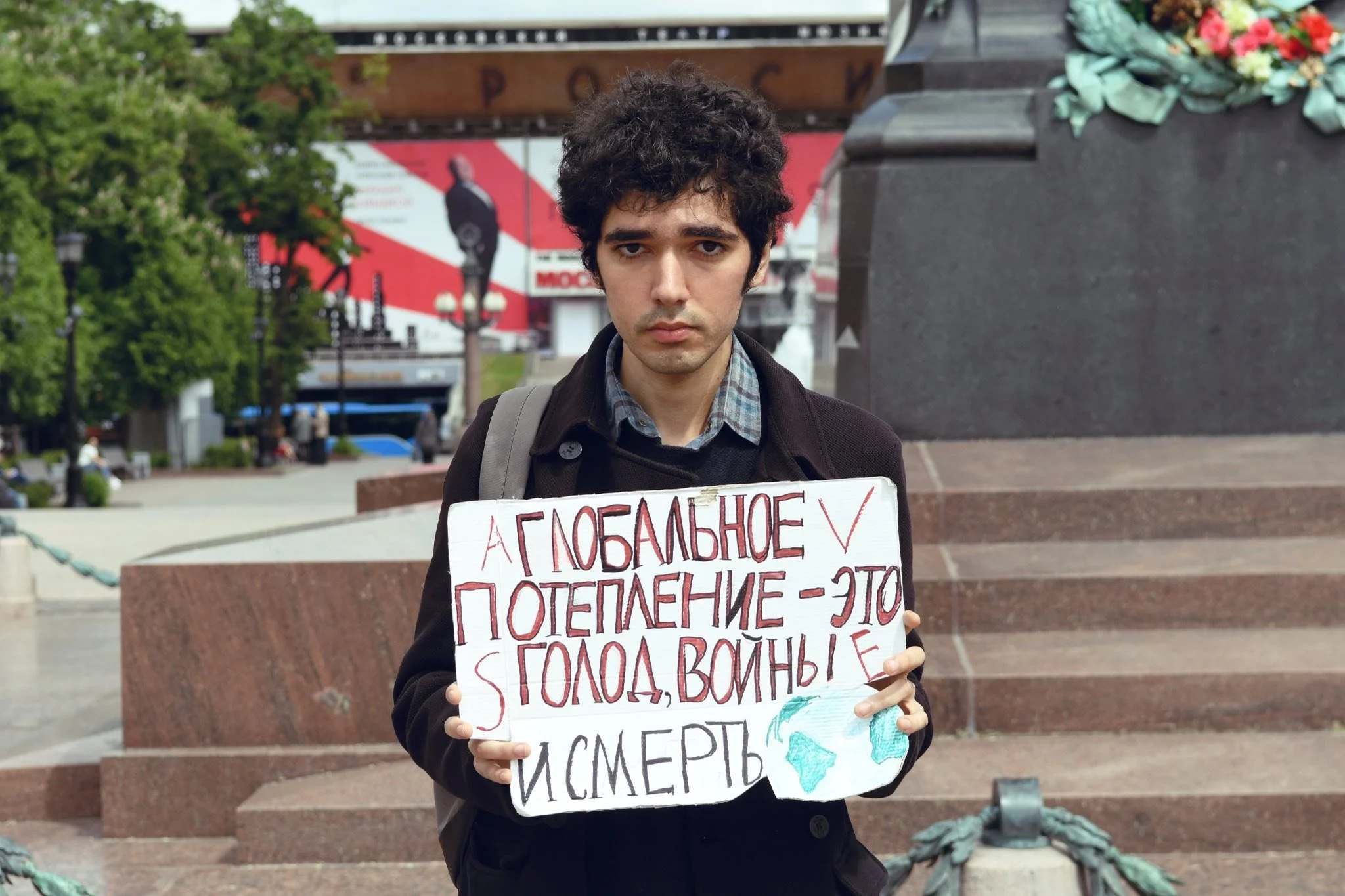

Arshak Makichyan

Youth activist | stripped of Russian citizenship in 2022

"I was stripped of my only citizenship for demanding climate action."

Anastasia Fomina

Defender from Arkhangelsk

"I changed my whole life to fight for climate justice. Now I want to see what justice really looks like."

Vitaly Servetnik

Environmental and human rights defender | Environmental Crisis Group

"We brought this case not just for ourselves but to show the world what is really happening and to challenge the lies told by those in power."

Vladimir Slivyak

Veteran activist, co-chairman for Ecodefense | Right Livelihood Laureate

"The Russian government tried to silence me and they labeled me a ‘foreign agent’, but I didn't stop. Because the most important thing right now is to save the climate. There is no time to fear."

Dariana Gryaznova

Human rights lawyer in exile

"When the courts take too long, repressive regimes take advantage."

Grigory Vaypan

Human rights lawyer in exile

"Many of our applicants have already paid a high price for bringing this case. If the judges ignore it, they’re rewarding retaliation. This will be a victory not for law, but for fear."

Liubov Samylova

Human rights defender

"The Court must act now — there is no time left to postpone the climate crisis."

Anonymous

Human rights activist

"The European Court was created to protect the vulnerable. The time is now."

Ecodefense

Ecodefense is the Russian environmental group established in 1989. The Russian government closed it down through the court in 2024, and it now works in exile.

Pavel Sulyandziga

Udege indigenous defender

"As an Indigenous Udege leader, I was exiled for defending my land. This case is our fight for justice."

Moscow Helsinki Group (MHG)

The Moscow Helsinki Group (MHG), founded in 1976 by Soviet dissidents to monitor compliance with the human rights provisions of the Helsinki Final Act, became the oldest and one of the most influential human rights organizations in Russia. Despite decades of persecution and its forced liquidation in 2023, it remains a symbol of moral courage and continuity between Soviet-era dissent and modern civil society.

timing is everything

Russia is the 4th biggest greenhouse gas emitter on the planet and it intends to keep increasing its emissions right up to 2035

This case has already been delayed for over 2 years

Applicants have been punished by the authorities for standing up for climate: NGO’s have been shut down; individuals have been forced into exile; some have been labelled “foreign agents” and one has even lost his citizenship - yet they keep resisting for as long as they can

A ruling from the European Court of Human Rights would be the first legally binding judgment on Russia’s climate record: it is likely to be the last opportunity to scrutinise Russia’s climate actions against international standards and set out clear steps to remedy the situation before it’s too late

Even if Russia doesn’t comply immediately, such a judgment can be used at COP negotiations, trade forums and beyond. Anywhere where Russia still participates on the international stage

When the regime in Russia changes, this ruling can help improve its climate policy without wasting more time

Add your voice, sign the petition.

When courts stall, repression wins. But if we act together, we can push this case forward. If you care about our shared future, now is the time to act.

One signature won’t change the world. But thousands of us, together, can. Add your name and demand that the Court act now.

Vladimir Slivyak, environmental activist, co-chairman for Ecodefense, Right Livelihood Laureate

“Putin is at war against Ukraine and he is at war against the global climate. We’ve got to stop him.”

Vitaly Servetnik, environmental activist

“The climate crisis is not waiting — and neither is repression. If the Court doesn’t act now, our case may be too late to matter.”

FAQ

-

A coalition of 18 individual applicants and 2 NGOs — including Indigenous persons and human‑rights defenders — is challenging Russia’s climate policies and actions for violating their human rights. After being rejected by all Russian domestic courts, they lodged the application (No. 9296/24) at the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) in September 2023. Since bringing the case, many applicants have faced repercussions (“foreign agent” designations, loss of citizenship, forced into exile).

-

The applicants pursued domestic avenues up to Russia’s highest courts and were rejected, leaving Strasbourg as the only forum with the authority to deliver a binding human‑rights ruling with potential to provide protection and justice for people in Russia and beyond.

-

Proceedings before the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) often take a long time. For this reason the Court has a ‘prioritisation policy’ which is intended to speed up the processing of “important, serious and urgent” cases. However, in contrast to other climate cases, in the Russian Climate Case there has been no prioritisation or communication to the State* nearly two years later. Every month of delay risks making any eventual ruling too late to prevent escalating global climate harms — repeating past patterns where the Court’s slow handling of “difficult” Russian cases negated meaningful impact.

* Prioritisation means the Court treats a case as urgent and deals with it more quickly than less urgent cases. See the ECtHR’s prioritization policy here: https://www.echr.coe.int/documents/d/echr/Priority_policy_ENG

Communication to the State means the Court officially notifies the government being sued and asks it to respond — the step that turns an application into a live case.

-

It is the first and only climate challenge by Russian citizens to Russia’s policies at Strasbourg. Given Russia’s withdrawal/expulsion from the Council of Europe and the repressive context for human rights and environmental defenders, this is likely the last such case within a legally binding international forum during the critical climate mitigation window.

-

Expert evidence shows Russia’s published policy from 2020 and 2021 allows emissions to continue rising to 2030 and only minimally decline thereafter — far above levels compatible with protecting human life and health or with Paris Agreement temperature targets. The Climate Action Tracker assesses Russia’s climate action as ‘critically insufficient’. The case argues that these policies breach constitutional and international human‑rights standards and Russia’s climate obligations.

Most recently, Russia has issued a new emissions decree providing for a weaker 2035 emissions target. The new target is about 22% greater than Russia’s reported 2021 emissions. -

Calculations cited in the case estimate Russia’s 2030 target to be 1.5–2.3× higher and its 2050 target to be 11.7× higher than a Paris‑consistent pathway. If replicated globally, this pathway implies ~4 °C warming by 2100.

-

Russia is ranked as responsible for the third largest cumulative emissions since the beginning of the industrial era. Currently, it is the fourth largest greenhouse gas emitter in the world and the second biggest source of global energy-related methane emissions. As of 2021, it was the world’s largest exporter of fossil gas, the second largest exporter of oil, the third largest coal exporter and the largest gas flaring nation. It has the world's second-largest coal reserves, and its 2020 Energy Strategy plans an increase in domestic coal production annually up to 2035. Russia has no quantifiable methane reduction plans and did not sign up to the COP26 global methane pledge. These factors materially affect global and Arctic climate risk.

-

Rapid Arctic warming, permafrost thaw and sea-ice loss on Russian territory threaten communities locally and drive global emissions and sea-level rise — making Russia’s policy choices globally consequential.

In 2022, the Russian government acknowledged (https://tass.ru/ekonomika/16334349) that the rate of warming across the country exceeds the global average by a factor of 2.5, and in the Russian Arctic zone by as much as 3.7.

Projections of Russian indicate that the area of near-surface permafrost within the Russian Federation will shrink significantly compared with the 1995–2014 baseline — by 22 ± 7 % under the SSP2-4.5 scenario and 28 ± 10 % under SSP5-8.5 by the mid-21st century, and by 40 ± 15 % and 72 ± 20 % respectively by the end of the century. (https://cc.voeikovmgo.ru/images/dokumenty/2022/od3or.pdf)

-

The application argues that Russia’s policies and actions violate the rights to life, health, home and family life (Articles 2 and 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights). It argues that the right to an effective remedy before a national authority has been violated (Article 13 of the Convention) and that the protection against discrimination in the enjoyment of the right to life and health has been violated in relation to youth applicants and Indigenous applicants (Article 14 taken in conjunction with Articles 2 and 8). Finally, under the Convention, the applicants argue that the Russian Government’s interference with their right to bring this case before the Court amounts to a violation of Article 34 of the Convention.